Imposing the risks offered by chemicals is a tough and imperfect business that reaches well beyond the scientific realm. There are many factors includes in balancing cost and advantage of such decisions that includes science, governments, industry and the public.

Our recent feature seemed at the continued debate around the risks of glyphosate – a herbicide that is one of the most broadly utilized agrochemicals in the world. Its use has end up becoming more controversial, especially since the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer discovered in 2015 that it is ‘possibly carcinogenic to humans’. Thousands of farmers have also been requesting its developer, Bayer–Monsanto, claiming the product is reliable for their cancers, with victories for both sides in a long-running series of legal instances. But in its periodic review of the chemical, the European Chemicals Agency (Echa) determined renew its approval in 2023, within a few limits, ruling that the product is secure and that there is no scientific basis for a ban. It might be reviewed again in 2033.

The case illustrates how imposing chance is a complicated and nuanced procedure. The difference in opinion among IARC and Echa, as an example, stems in part from the data sources utilize to reach their taxes – IARC uses only publicly available data, at the same time as Echa consists of data from producers – however it also displays Echa’s evaluation of the practical reality and whether ranges of real-world publicity are probably to be harmful. Then there are outcomes past human toxicology – for instance, the proof of damage to insect populations. Public opinion is likewise a key component that places pressure on policymakers – as soon as public sentiment has soured it could be tough, if not not possible, to opposite.

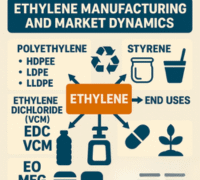

Glyphosate joins a long list of materials which have made the journey from utility to ubiquity after which notoriety. Despite enhancements in chemicals protection and risk assessment regulation over many many years, there frequently follows a similar pattern when chemicals leave the lab and marketplace forces take over. This is when assorted use or simply over-reliance can increase because a technology will become dominant, and glyphosate is definitely a victim of its success here. PFAS is some other current example – an extremely useful elegance of chemicals that has end up a synonym for environmental harm and whose utility would possibly now be lost to us as a end result. In the right place it is a material with out peer, but regulators now confronted with the assignment of responding to the harm posed by using its overuse are enforcing outright bans.

More responsive risk assessment approaches and better tools for toxicology, such as predictive models that may highlight whether a substance poses a risk, will assist to make this procedure more efficient. And so will chemists: their training includes understanding the risks in their work and in recent times many undergraduate publications additionally explicitly address the demand to enhance the sustainability of their practical – it’s now part of the Royal Society of Chemistry’s accreditation criteria for university courses.

What’s probably missing in the system in the meanwhile, but, is help or motivates to innovate and develop replacements. Switching to option pest control techniques or products, as an example, also comes with suggestive risk – not least the charges of funding, along with the burden of proving they are safe and effective. There also can be an unwillingness to have interaction with debates round specific materials if folks that depend on them sense there may be no better choice. If we hope to steadily replace chemicals with safer options, we need a system that allows development to locate those options and assist deliver them to marketplace. We should never find ourselves in the role that a product will become too big to fail.