First produced by French chemist Louis Jacques Thénard in 1818, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) has many uses. The chemical industry manufactures over 5-million tons of H2O2 per year, for products like disinfectants, bleaching agents or even rocket fuel. almost half of global H2O2 manufacturing finds its way back into other chemical methods, adding value to several chemicals via oxidation.

Today, the anthraquinone procedure– developed by BASF in 1939 – is the near-exclusive way of manufacturing H2O2. Hydrogen reduces anthraquinone – a cheap, broadly available organic reagent – in the presence of a palladium catalyst. Oxidation of the resulting diol with dioxygen regenerates anthraquinone, manufacturing H2O2 as a by-products. Aside from its ease of synthesis, the only by-product of H2O2 oxidation is water, restricting environmental effects.

Make it where it’s needed

To lower transport and storage costs, providers concentrate H2O2 to around 30–70%, whereas most users need concentrations under 10%. This wastes energy, makes use of big amount of water to re-dilute appropriately and increase concerns about operating with such concentrated oxidant. ‘Minimizing the use of finite resources and preventing the formation of pollutants should be a big target [going forward],’ says Richard Lewis, entrepreneurial lead of Hydro-Oxy.

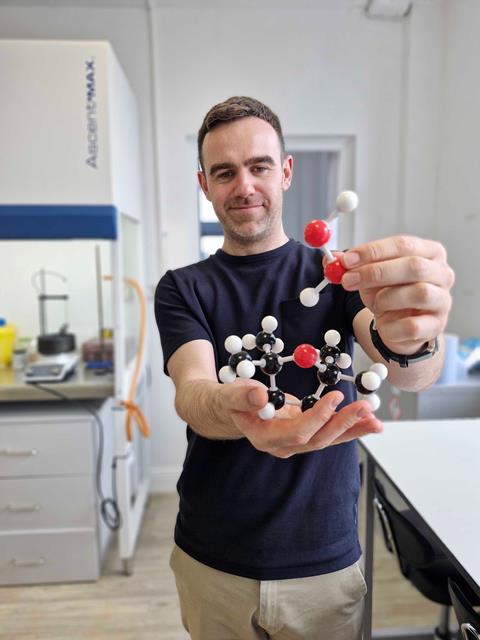

Housed in the Cardiff Catalysis Institute, UK, Hydro-Oxy targets to conquer these issues by producing H2O2 in-situ. Its technology uses a palladium-based composite catalyst to convert dilute concentrations of hydrogen and oxygen – of similar levels to that formed by using electrochemical water-splitting – into hydrogen peroxide. Doping the catalyst with additional metals such as gold and platinum can enhance the activity and stability of the catalyst.

The corporation has typically used the technology – with the addition of ammonia – to synthesise cyclohexanone oxime, a main intermediate in generating caprolactam, the monomer for polyamide-6. The method can be tailored to other commodity chemicals– consisting of propylene oxide, methanol and phenol. Hydro-oxy’s technology creates yields nearly 100%, lowers materials costs by up to 15% and reduces energy intake by up to 30%. Lewis describes that this makes in-situ hydrogen peroxide manufacturing ‘a ways more economically competitive to current industrial techniques’.

‘The benefit of our system is that it can be integrated into present [industrial] infrastructure, which lowers the limitations to entry,’ stated Lewis. Under industrial situations the use of focused reagents, the catalyst can last for over 100 hours in stream and has an overall lifetime of round 18 months.

‘We’ve showed in house that we cable to achieve a multi-litre scale and we’re presently beginning experiments at a 20-litre scale with partners based in Beijing,’ stated Lewis. He adds that this is feasible because of the help from industrial partners, along with Johnson Matthey.

Organic variations

‘Lots of water in an organic procedure isn’t always good news. Many organic molecules are not soluble in water… or they react,’ describes James Clark, co-founding father of Addible. He provides that industry has overcome this problem using of biphasic systems, where organic substrates react with hydrogen peroxide on the boundary among organic and aqueous solutions. Clark describes that a mixture of a tungsten-primarily based catalyst and a phase switch catalyst for advanced communication between the layers results in ‘a quite complex soup, which is a far way from ideal’.

Addible is aiming to streamlines the technique by taking H2O2 out of water. The corporation – a spin-out from the University of York, UK – had to begin with verified tetramethyloxolane (TMO) as a green solvent that could replace toluene, that’s carcinogenic. TMO is just like tetrahydrofuran, however with four methyl groups blocking the carbons adjacent to the oxygen atom.

Computational characterization disclosed that TMO is very good at hydrogen bonding. ‘If you’re taking standard aqueous hydrogen peroxide and shake it up with TMO, a hydrogen bonded complex forms,’ stated Clark. ‘It’s a vast entity with pretty strong bonding.’ The complex – known as TMO2 – is strong over long periods and solubilizes most natural compounds. Addible can recently produce TMO2 on a 10-litre scale, and its parent solvent TMO on a 1 ton scale.

TMO2 has up to now oxidized a wide range of compounds in non-aqueous conditions, which include alkenes, aldehydes, organic sulfides and amines. Clark notes that the activity is mainly lower than other strategies, moreover addition of a non-metal catalyst improves the system. While Addible’s technology doesn’t remove the need to produce H2O2 within the first place, it solves an existing problem within industry, making safer, more effective and reduces overall costs.

Other chemists have earlier surpass the problem of water in such reactions by using of organic peracids – made by oxidising carboxylic acids. Such molecules are common, however their instability can make them risky, with a some restrictions now restricting their transport. Carboxylic acids reformed as unwanted aspect products can also create excess waste.

The corporation has worked with several corporations in the green chemistry space to finance its technology. Aside from oxidation of small molecules, Addible is now looking to make bigger into recycling rubber tyres and different polymers discovered in textiles and plastic packaging.

‘Imagine a system where you’re making hydrogen peroxide the use of a modern method, like electrochemistry, or photocatalysis, producing it in-situ, and the TMO2 is extracting it because it’s formed,’ says Clark. ‘Then you have a definitely continuous system.’